Milorad Pavić (1929-2009)

I picked a copy of Dictionary of the Khazars off a library shelf back in 1993, one of those acts of book snatching that usually bears no fruit but occasionally alters my whole perception of that cultural endeavour called 'Literature'. I was instantly enthralled by the novel's cascade of ideas and startling images, all rendered in a stunningly original prose style that made use of blisteringly strange and convoluted metaphors and similes. Added to this was the playfully experimental nature of the novel itself. Two versions, one male, one female, that differed only in a single paragraph, but a paragraph that supposedly changed everything about the story. It wasn't even essential to read either version from beginning to end, for both were constructed in such a manner as to be satisfactorily read in a non-linear progression. As if all this wasn't enough, the story told by the book was remarkable too: the historical moment when the mighty Khazar Empire decided to discard its old culture and accept a new one overnight...

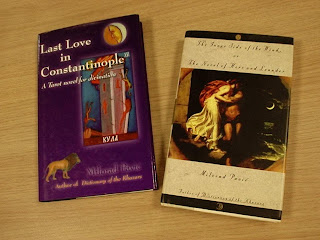

So much for Dictionary of the Khazars. Despite its genius, I actually rate it as the weakest of Pavić's novels. Which means that the others are even better; an astounding achievement in the context of 20th Century literature. My favourite of all is probably Landscape Painted with Tea, set in the anachronistic theocracy of modern-day Athos. I have also a deep and abiding affection for The Inner Side of the Wind (surely one of the most poetic titles for any novel), a trans-temporal love story that is almost formally odd and yet contrives to be as ultimately moving as the most poignant works of this surprisingly extensive sub-genre (I'm thinking of excellent works in a broadly similar vein by Robert Nathan and Jack Finney). Even here, Pavić does not succumb to the (overrated) temptations of linearity. The Inner Side of the Wind is a two part story and both parts are printed back to back, thus the tales (and the lovers) meet in the middle and only truly there; content and form have been alchemically transmuted into one substance.

When it comes to my own work, Pavić provided inspiration for ideas and forms as well as language. There was a time when I tried far too hard to write like him. The zenith of my Pavić worship produced such tales as 'Spermaceti Whiskers', 'Thanatology Spleen' and 'Muscovado Lashes', where I give the impression of thrashing about in a box of pataphors. I eventually climbed out of that box because I knew my skills weren't pure enough for the task: the strain of being relentlessly original was too intense. And the world didn't need a cutprice Pavić: it already had the real thing. And yet, without my discovery of Pavić my confidence to be daring with the English language would be vastly smaller. I will always be grateful to him for showing me the way to this freedom.

1 Comments:

Thank you for this, Rhys...

I am feeling so sad, and this truly helps. It is a fine tribute to a great and moving experimenter. I know that the kind of surprise and enchantment in Milorad's work lives in yours.

Post a Comment

<< Home